Lying in Wait: PTSD in the Older Population

Post-traumatic stress disorder is usually thought of as a conditionrelated to the military. But research is finding that PTSDcan be prevalent in older populations.

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) has become something of a buzzword in recent years, given the ongoing conflict in the Middle East and the impact of this war on the younger generation. While the increased attention to PTSD in the media has been beneficial in bringing this important issue to light, it has also resulted in a somewhat narrowed view of PTSD as only affecting a specific part of the population—young adults who have been to war. This is unfortunate, because PTSD is a global disorder that occurs across the lifespan.

What is PTSD?

It is currently estimated that 8 percent (roughly 25,112,000) of the U.S. population meets the criteria for PTSD (Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety n.d.). A wide range of traumatic incidents can lead to PTSD. Any event in which a person is exposed to “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence” (APA 2013) can lead to PTSD. Examples include: combat exposure, sexual assault, car accidents, natural disasters, and mass shootings. This traumatic exposure is what is known as a Criterion A stressor, according to the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Exposure to a Criterion A stressor does not guarantee the development of PTSD; development of PTSD comes when a Criterion A stressor sparks the onset of symptoms in four additional categories: intrusive symptoms (nightmares, memories, flashbacks), avoidance symptoms (isolation, withdrawal), cognitive symptoms (negative emotions, guilt), and arousal symptoms (being hypervigilant, easily startled, on edge) (APA 2013). The range of exposure to at least one traumatic event during their lifetimes is the highest in adults aged sixty-five and older, ranging from 70 percent to 90 percent (Creamer and Parslow 2008), making older adults one of the most vulnerable populations to the condition. PTSD is rarely a stand-alone diagnosis. It is most commonly diagnosed with “comorbid” conditions—those that are naturally related to the experience of PTSD, such as depression and substance abuse.

PTSD in Older Adults

Aging populations are uniquely vulnerable to PTSD for a broad range of reasons. The transition to older adulthood comes with a series of changes that can be significantly stressful. These include but are not limited to, reduction in income, changes in identity with retirement, decreased mobility and physical strength, widowhood, declining social support, and slowing or diminished cognition (Cook 2001; Kaiser et al. 2014). Where many of these stressors do not constitute a Criterion A stressor and therefore are not PTSD-inducing, many will exacerbate pre-existing trauma and bring symptoms of PTSD to the forefront for the first time in an older adult’s life. Older adults often have dormant traumatic symptoms that occasionally flare throughout their lifetimes, but usually did not overtly interfere with everyday life.

The stressors inherent in the transition to older adulthood may serve as catalysts for the onset of PTSD in older adults. For those who have had PTSD for most of their lives, many are able to “manage” their symptoms independently without the assistance of medication or mental health providers through will power, avoidance (example: isolating themselves socially), or distraction (example: working excessive hours). When cognition slows, physical abilities weaken, distractions like work fade with retirement, and social support systems are lost or reduced, the symptoms of PTSD that older adults were once able to “manage” may become unmanageable. It is also important to note that many of our current older adult population experienced trauma prior to the advent of the diagnostic terminology for PTSD, developed in 1980. This has resulted in their PTSD going undetected or untreated for years due to lack of knowledge of the disorder at the time of trauma (Cook 2001).

Symptoms

Much of the research done into PTSD in older adults demonstrates that the experience of trauma, as well as symptoms in response to this trauma, differ between younger and older adult populations (Kaiser et al. 2014). Symptoms tend to present in older adults as more physical in nature such as aches and pains, gastrointestinal problems, fatigue, and cognitive difficulties such as problems with focus, attention and memory (Hermann 2014). Older adults are more likely to describe their problems as related to stress or call them issues, rather than specific psychological or trauma-focused language, like saying, “I’m feeling anxious.” PTSD symptoms in older adults tend to be less persistent over time (Cook 2001)—they ebb and flow more. For example, having good and bad days, weeks, and months, rather than always feeling anxious. This is likely due to the impact of factors like the amount of time since the event, culture (example: believing hardship is inevitable and should be endured), and past traumatic experiences that may have served to offer perspective.

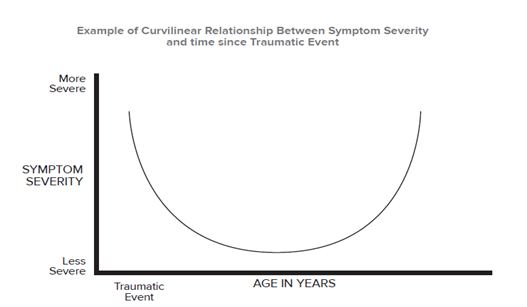

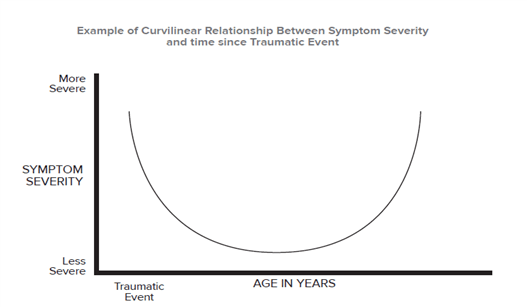

Research has shown that as many as forty-five years post trauma, older adults meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Falk 1994). Studies done on aging populations often demonstrate a curvilinear relationship. That is, symptoms are highest after exposure, decline for years, then increase later in life (Port, Engdahl, and Frazier 2001). Older adults with PTSD may begin to show symptoms the first time in older adulthood or have a recurrence of symptoms from long-ago traumas as a result of the impact of recent stressors.

Recognition, Treatment, and Support of Older Adults with PTSD

Recognition of PTSD in older adults begins with knowledge of the prevalence of lifetime exposure to trauma in the older adult population, awareness of the variable nature of symptoms, and the potential for late-life onset due to the unique stressors inherent in the transition to older adulthood. As symptoms of PTSD and its related diagnoses (depression, substance abuse) manifest in older adults, it is important for family members and people in supportive roles (CSAs, doctors) to notice them and aid in organizing treatment and support.

Treatments for PTSD come in the form of both medication and supportive therapies. Many of the drug trials that led to development of medications approved for PTSD did not include older adults, and therefore the medications can be unpredictable in older populations (Hermann 2014). Antidepressants known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—for example Zoloft, Paxil, Lexapro—have been shown to help with some of the symptoms of PTSD. However, evidence has consistently demonstrated that therapy is most effective in treating symptoms of PTSD (Hamblen 2010).

There are multiple evidence-based treatments (EBTs) that include cognitive processing therapy (CPT) (Resick, Monson, and Chard 2008), and prolonged exposure therapy (PE) (Hamblen 2010). The two techniques have significant overlap, with CPT attempting to change the thoughts associated with the trauma, and PE attempting to change the emotions and physiological reactions to the trauma. Both have been shown to be effective in treating more immediate trauma in younger populations. However, older adults are less likely to approach their trauma from a psychological perspective (the way they think and feel) and are more likely to relate their symptoms to outside events and stressors (loss of income, loss of a spouse). (Hermann 2014). Older adults may also have cardiac or respiratory problems that make intense trauma-based treatments dangerous.

Assessment of PTSD in older adults should include questions about symptoms, distant and recent trauma, as well as screeners for cognitive decline that may be contributing to or exacerbated by the symptoms. If trauma or PTSD is suspected, older adults should be referred to a therapist with knowledge of trauma, the unique problems of older adults, and necessary adaptation of interventions for working with older adults (APA 1998). Effective forms of treating trauma in older adults focus more on finding meaning, and helping patients organize and examine memories throughout their lifetimes. Patients may benefit from integration of their trauma history into this life examination with the aid of a therapist to help in processing memories and coping with changes resulting fromtrauma (Cook 2001).

Many older adults have lived with their trauma for years. Over time, they learned methods of coping, both healthy (relying on social support) and unhealthy (drinking alcohol), over the course of their lifetimes. Good treatment of PTSD will incorporate existing strengths and healthy methods of coping, and aid them in supplementing the more maladaptive methods of coping or methods they have lost (example: engaging in local community groups for social support following the loss of a spouse).

Perhaps the most unique and important component in the treatment of PTSD in older adults is education, support, and methods of coping for the caregivers and family members who are a part of the person’s daily life, and will aid in the treatment and recovery. PTSD has a lasting social impact. Caregiver stress is particularly high in people who care for older adults with symptoms of PTSD, warranting additional support and education for them to be able to cope with the vicarious effects of supporting someone who has a trauma history. CSAs and other advisors are well positioned to advise and guide their clients to appropriate professionals for help. • CSA

Carilyn Ellis is a Fellow at the Boise VA Medical Center, specializing in oncology, palliative care, and primary care psychology. She completed her doctorate in clinical psychology at George Fox University in Newberg, OR. She loves serving those who serve our country, and especially loves working with Veterans. She can be reached at [email protected]

Lying in Wait: PTSD in the Older Population was recently published in the Summer 2014 edition of the CSA Journal.

Reprinted by Always Best Care Senior Services with permission from Senior Spirit, the newsletter of the Society of Certified Senior Advisors The Certified Senior Advisor (CSA) program provides the advanced knowledge and practical tools to serve seniors at the highest level possible while providing recipients a powerful credential that increases their competitive advantage over other professionals. The CSA works closely with Always Best Care Senior Services to help ABC business owners understand how to build effective relationships with seniors based on a broad-based knowledge of the health, social and financial issues that are important to seniors, and the dynamics of how these factors work together in seniors’ lives. To be a Certified Senior Advisor (CSA) means one willingly accepts and vigilantly upholds the standards in the CSA Code of Professional Responsibility. These standards define the behavior that we owe to seniors, to ourselves, and to our fellow CSAs. The reputation built over the years by the hard work and high standards of CSAs flows to everyone who adds the designation to their name. For more information, visit www.society-csa.com

To print this article CLICK HERE